Steve's Guide To Mixing Drums - www.drum-studio.com

Intro:

As with anything related to music, audio, and making records, there is no ONE way to do things, but I felt that it might be helpful to have this information out there. I'd advise anyone mixing to use this as a starting point, and from there it can be tweaked and adjusted to suit the sound you're looking for.

Overview:

I typically use 11 microphones to record drums --

2 Kick Drum mics -- one inside the drum, one outside

2 Snare mics -- one over the top head, one under the bottom head

2 Overhead mics (Left and Right)

2 Room mics (Left and Right)

3 Tom mics -- one for each of the 3 toms I use

Record Levels:

I record everything, for the most part, to an optimum volume level -- meaning that all the drum mics are recorded as loud as they can be without clipping or distorting. Naturally, though, when I'm not playing a drum, it's mic's response is very low, and only when I hit the drum does it go up to it's desired level. This allows for a uniform sound from the get-go. In fact, leaving all the drums at 0dB (pictured), is not a bad sound at all, it's just not as clean as it can be.

Panning:

For almost all recordings, I leave the 2 Kick mics and the two Snare mics in the dead center. The two Overheads go 100% Left and 100% Right respectively, as do the Room Mics. The Toms get spread out from left to right, Tom 1 being 100% Left, Tom 2 being about 50% Left (or even center), and Tom 3 being 100% Right. All of these pan settings can be adjusted in literally dozens of ways, but it seems to work well for me, most of the time, to have them this way.

Mix Levels:

For a typical, balanced drum sound, try out these volume levels.

Kick 1: 0dB

Kick 2: -4dB

Snare top: 0dB

Snare bottom: -6dB

Overhead Left: 0dB

Overhead Right: 0dB

Room Left: -7dB

Room Right: -7dB

Tom 1: -2dB

Tom 2: -2dB

Tom 3: -2dB

EQ:

EQ (Equalization) is the type of post-production that I use the most, and along with compression, is the only plug-in I usually apply to my recordings. There are many different ways to EQ a drum mix, so I'm just going to give you my typical settings and the reasons behind them.

Kick 1: This mic picks up most of the body ("boom!") of the kick drum and doesn't need much low end added to it to make it sound big. I tend to get rid of some of the mid-frequencies though, to clear up the sound (you'll notice that I do away with many of the mid frequencies). A typical EQ curve looks something like this:

Kick 2: This mic gets also a lot of low end, but picks up more of the kick pedal beater hitting the head, and produces a lot more "snap!" than Kick 1. I usually EQ this channel to accent the high end properties and find that it blends well with Kick 1 this way:

Snare Top: This mic picks up the sound of the stick hitting the snare drum, and should give an overall representation of what the snare sounds like up close. I tend to find a "sweet spot" in the high frequencies that allows the character of the snare to really pop out, while getting rid of some of the muddiness of the mid frequencies:

Snare Bottom: This one is much trickier and really depends on the song, you can either have too much high end, or not enough depending on how the song sounds around the drums. Or you can just leave it be, this is a good one to experiment with, without much input from me.

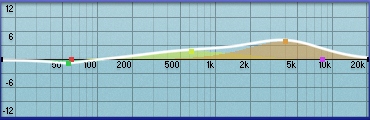

Overheads: Both overheads will respond slightly different to the same EQ, but there's a typical rule that I follow that has always suited me nicely...gently lift up some of the high end, and gently get rid of some of the mids:

Rooms: Like the overheads, the room mics shouldn't be treated exactly the same way, but they're usually very close together in their EQ'ing. Try getting rid of some high end, and accentuate the mid-low end. This fills out the kit nicely because there's so much high end and so little mids in the rest of the kit, that adding some into the rooms makes for a nice balance:

Tom 1: I have pretty specific ways of making my toms pop out, and you'll also notice that getting rid of mids, raising high and low ends is the key to this:

Tom 2:

Tom 3:

Compression:

I tend to limit the amount of compression I use, and always to try to apply gently when I do. The reasons for this are:

- The drums will likely be compressed again sometime in the mixing/mastering process after I've given up control of it.

- Compressed drums typically sounds better by themselves but lose something when mixed in with other instruments.

- I think over-compressed drums sound dated and genre-specific.

With that being said, I do typically compress the Room mics and the Snare top mic. There's no intellectual reason I do this, I just think it sounds better that way. The overheads certainly can be compressed as well, but I avoid that unless I feel the drum mix needs a little extra "pump". I almost never compress the kick mics or tom mics; I just do not feel it's required for those, most of the time. I personally do not spend too much time with specific compressor settings, because my mix is hardly ever the "final mix," I just do what sounds good to me at the time. This usually involves cycling through presets until something clicks in my ears. I'll leave it to mix engineers of the whole song to decide how much or little compression to add to my initial ideas.

Reverb:

Reverb is certainly something that is used a lot on drums, but it's so specific to the song that it makes no sense to discuss it at length here. At best, the drums I record don't require reverb to sound "good", that is something I am quite sure of. But if you did want to add reverb, I would recommend adding it to the Snare bottom (for a reverb'd snare sound) and to the Room mics (for the illusion of being in a bigger space).

That covers it for my thoughts on mixing my drum set. Good luck and don't be afraid to experiment!

-Steve Riley, drummer (www.drum-studio.com)